Candle Altar

- The Creation of an Artifact to Facilitate Spirituality

Technical Report IRC#1997-099

November 10, 1997

Babel - New Media Experiment 2

Oliver Bayley & Sean White

bayley@interval.com

swhite@cs.stanford.edu

Candle Altar

- The Creation of an Artifact to Facilitate Spirituality

Technical Report IRC#1997-099

November 10, 1997

Babel - New Media Experiment 2

Oliver Bayley & Sean White

bayley@interval.com

swhite@cs.stanford.edu

Table of Contents

1.0 Introduction.....................................................................................................................

2.0

Design Brief.....................................................................................................................

3.0

Initial Idea Exploration....................................................................................................

3.1

Ideas.............................................................................................................................

3.2

Idea Selection................................................................................................................

4.0

Initial Concept Description..............................................................................................

4.1

Usage Scenario..............................................................................................................

4.2

Benefits to the User........................................................................................................

4.3

Issues to be Resolved.....................................................................................................

5.0

Development...................................................................................................................

6.0

Final Concept Description...............................................................................................

6.1

General.........................................................................................................................

6.2

Technical.......................................................................................................................

6.3

Appearance...................................................................................................................

6.4

Interaction......................................................................................................................

7.0

Lessons Learned.............................................................................................................

7.1

User Feedback...............................................................................................................

7.2

General observations......................................................................................................

7.3

Possible enhancements and conclusions........................................................................

Appendix

A: Design Development......................................................................................

A1

Content........................................................................................................................

A2

Technical......................................................................................................................

A3

Physical.......................................................................................................................

A4

Initial Public Release and Revisions................................................................................

Appendix

B: Guest Comments............................................................................................

Appendix

C: History of Candle-making and Candle Industry Facts .....................................

Appendix

D: Exhibition Hand-out........................................................................................

Special thanks to:

Greg Beattie - Carpentry

Chris Seguine - Lighting

The following report documents the activities, process and learning which occurred during the production of an artifact intended to facilitate spirituality. The work was commissioned by the Babel project as part of their second New Media Experiment (NME2). The team members were Oliver Bayley and Sean White. The final artifact was installed in the Interval Research CAVE as part of an exhibit of NME2 designs. The altar was in use for approximately two weeks at the end of October 1997.

The following design brief was presented to participants in the NME2 by the Babel Project:

“In order

to learn more about the interaction between spirituality and new media technologies,

Babel is asking volunteers to generate and implement designs for technological

artifacts which facilitate spirituality. The design space is wide open as long

as the design can facilitate a spiritual practice, a spiritual experience, or

both. Don’t worry about designing something that is universally appropriate. Participants

can, and perhaps should, design something that is personally relevant. However,

participants should be prepared to explain why your design works for you, including

how it relates to your spiritual beliefs.

Final

designs are due 9/26 for inclusion in a Tuesday Seminar and the Babel Project

Review. If you want to participate, please be prepared to describe your design

in detail before you begin implementation. The project has some funds budgeted

for materials, but we’ll need to make sure we have enough money to pay for all

the designs. If you need grist for the creative mill, check out the notes from

the brainstorming session we had in July. The notes are available on the Babel

web site.”

After receiving the design brief, we began the process by brainstorming a wide variety of possible design directions. In retrospect, we were already predisposed towards a visual experience because of our work in other projects (e.g., Casablanca) and our combined design backgrounds. Neither of us were very spiritual so we wanted to put extra care into making sure we stayed close to the heart of the design brief. We were also intrigued by the notion of an altar or similar object that would be situated and allow a guest to approach spiritual practice as a place.

Some of our initial ideas involved holding still and meditating in front of the altar to get a desired effect, such as transforming the guest’s image or the background. Another set of ideas involved putting a prayer, hope, or dream onto a piece of paper or similar object and using technology to both capture and destroy the object—the destruction of prayer objects being an established practice in some cultures. We also explored focus practices (e.g., meditation) where the hands would be placed on the altar and visual images reminiscent of the “powers of 2” video would be triggered based on how long the guest was able to stay.

As inspiration we listed some of the tools that are already in use, which facilitate spiritual practice today. These included items like: containers, death poetry, the Koran, the Bible, the Cross, the Star of David, menorahs, specific rituals, altars, rosaries and candles. We also listed some common catalysts and characteristics of spiritual practice separate from specific religious symbols. Some of these were scale, perspective, panorama, raw-ness, risk, pulling focus, isolation, places, sounds and journeys.

After completing the initial brainstorming, we evaluated the ideas and lists. The notion of an altar as a means of creating a spiritual practice was a consistent theme in our work. We also found the notion of a candle as the primary user interface to be very compelling. A number of the other concepts were equally interesting, but we felt that the notion of a candle-based altar would allow us to maintain the spiritual theme of the design.

The candle altars in churches inspired us because they embody a number of characteristics which we felt important; spiritual value, visual interest and appeal, nearly random candle arrangement and status (lit, half burned, out) and compelling interaction (lighting and extinguishing candles). We believed we could leverage off some of these characteristics and introduce a few new ones to create a new kind of experience.

One of the interesting things about candle altars is the fact that every candle has a story to tell. Wouldn’t it be interesting if that was available for other people to hear? How would that effect the reasons why people light a candle? Candles are often lit to commemorate cyclical, recurring events. What if the commemoration was automatically performed every cycle?

4.0 Initial Concept Description

The following section describes the experience we set out to produce. At this stage, not all of the details had been decided upon.

A person lights a candle and leaves a message (audio, video, or paper) which can be seen/heard by others. The process involves the real lit candle transitioning into a virtual candle displayed on a monitor. The virtual representation of the candle will remain for the rest of the day and then appear at predefined intervals. The person can select one of three intervals at which the message will reappear by choosing a candle representing daily, monthly or yearly commemoration. As time goes by, the altar will gather a collection of candle messages that will appear on the display according to their creation date and repeat cycle.

The candle altar was intended to provide people with the means of externalizing a problem or event that had spiritual significance to them. While traditional candle altars enable the commemoration of an event, the ritual is a very private one. In the Catholic religion, confession serves as a form of externalization, but it is focused on sin. We thought that there may be things which people would want to ‘make public’ in an anonymous way which they would not otherwise do with friends, relatives or counselors. As well as contributing to the collection of ‘messages’ they could also listen to someone else’s ‘message’ and perhaps learn that they are not the only one with a particular problem. It should be said that we also intended for people to use the altar for positive events so that over time, the altar would accumulate a diverse range of messages. We would hope that people would use the altar on a regular basis and build a kind of relationship with it, perhaps treating it as a living being with a collective human soul.

· How does the artifact reset itself ready for the next person - manually by the user, by a ‘caretaker’ or automatically?

· What is the nature of the message (audio, video, other)?

· How does the person input the message - interaction, controls, instructions?

· How does a person retrieve a message?

· How are the candles represented on screen including their behavior and differentiation?

· When and how does the departure from real to virtual occur?

· What factors will influence the visual interest value of the artifact?

Only two weeks were available in which to design and build the artifact. To meet this tight schedule it was necessary to work in parallel and it also meant that we were limited to making or using items that we could build or obtain very quickly.

The activity can be broken down as follows:

1. Define content

2. Define technical solutions to support functionality of artifact

3. Design and build physical structure

4. Implement functionality (electronics and programming)

5. Design graphical content

Steps 1 and 2 were interdependent as we had to find the best fit of technology and content given the time-scale. Steps 3 and 4 were major tasks that were addressed in parallel.

For detailed descriptions of tasks and the evolution of the design refer to Appendix A: Design Development on page 9. This includes a section describing the problems encountered when the artifact was first exposed to real people and the way we improved it.

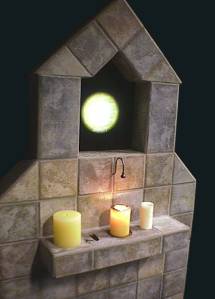

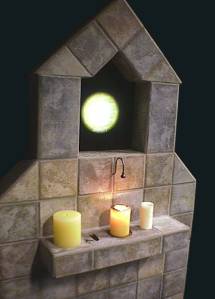

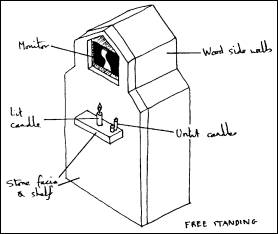

The artifact is apparently built of stone, and the main features are an alcove and a shelf. The structure is reminiscent of a church; its profile resembles a steeple, the apex resembles a pediment. When it was situated in the CAVE, lighting accentuated these features. At the back of the alcove is a display with a number of representations of flames slowly moving against a black background. On the shelf are a copper disc positioned in the center, three unlit candles of different sizes to the left, and matches with a striker to the right. The only other feature is a copper, faucet-like fixture mounted about 9 inches above the copper disc.

People can interact with the altar in two ways:

Commemorating

an event

A person approaches the altar and places an unlit candle on the copper disc. They are prompted to light the candle, then leave a verbal message. When they have finished they blow out the candle and remove it from the disc. The message they have left is represented by a flame on the display in the alcove. Their choice of candle defines the repeat cycle for the message’s appearance in the future. E.g., if the medium-sized candle is used the message will appear for one day every month. The small, medium, and large candles represent daily, monthly, and yearly repeat cycles respectively.

Learning

about an event

A person approaches the altar and touches any flame displayed to hear the message left to commemorate an event.

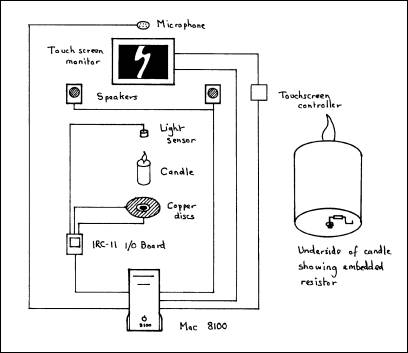

The altar’s “system” consists of the following components:

· Macintosh PowerPC 8100 running a Director 5 movie

· 17” CTX touch-screen monitor

· Microphone and speaker

· IRC11 I/O board connected to

~ the Mac

~ photo-electric cell

~ open circuit bridged by resistors embedded in candles

The system is further described by the following schematic:

The following paragraphs describe sub-systems which may contain intellectual property (IP) proprietary to Interval Research:

Initiation of task using detection and recognition of a candle - Embedding of resistors into the base of candles which when placed on concentric copper rings complete a circuit and enable the IRC11 to measure the resistance. This leads to an image confirming type of candle and an audio prompt instructing the user what to do next. Should the user complete the circuit with their hand they will hear an instruction to place a candle on the rings.

Use

of unique identity tangible objects (candles) to simplify the user interface -

Three candles of differing size, recognizable to the system by unique resistance

values of resistors embedded in their base, were used to determine the repeat

cycle with which candles are displayed on screen.

Control of audio recording using flame detection - If a candle placed on the copper rings is lit, a photo-sensor above will detect the flame and the system will begin recording. When the flame is extinguished (blown out) recording will stop and the audio is played back to the user. They will be instructed to a) re-light the candle if they want to change the message or b) remove the candle from the rings to complete the task and hence store the message in the system. The key to the reliability of the flame detection system was an algorithm to constantly check ambient conditions and contrast them with flame events, which were also sampled for consistent values before beginning recording.

Unpredictable (serendipitous) display of message placeholders based on combination of creation date and repeat cycle value whose messages can be heard by touching the screen image - On any given day, the number of message flames displayed will depend on the day they were created and the candle (daily, monthly, yearly) used to create them.

[this space left blank intentionally]

|

|

|

|

|

|

The following table describes how the user should interact with the artifact and it’s resultant behavior, including system status.

| Screen: [User: [Prompt: | Flame representations slowly moving around the screen Bridges copper disc contacts by touching with hand (or other object) accidentally] “Choose a candle and place it on this disc”] |

|

| User: System: Screen: Prompt: | Choose candle and place on copper disc Detect and identify candle Candle representations disappear and large graphic of candle appears with label (Daily, Monthly or Yearly) “Light the candle and leave your message. When you have finished blow it out” |

|

| User: System: Screen: Prompt: System: | Light candle Determine if candle is alight Candle graphic glows yellow “Begin speaking now” Start recording |

|

| User: System: Screen: Prompt: | Speak message and then blow out candle Stop recording and playback user’s message Yellow glow disappears to reveal a small flame (‘inside’ the candle graphic), a representation of the user’s message “If you are unhappy with this, light the candle and start again, otherwise remove the candle” |

|

| User: System: Screen: | Remove candle Detect absence of candle Flame representation moves left off the screen, the candle graphic disappears and the original flame representations reappear |

|

Three questions were posed to people who attended the NME2 exhibition:

· Do the designs have any bearing on your spiritual beliefs?

· Could they be a part of your spiritual practice?

· Did you have a spiritual experience while using them?

For actual written responses refer to Appendix B: Guest Comments. Despite their misgivings about various aspects of the altar, many people did express a positive interest in the concept and the issues it raised. However, people generally felt uncomfortable about disclosing their private thoughts while using a public installation. Firstly, they felt that the environment in the CAVE was not private enough to actually speak/whisper their message. Secondly, they were concerned that their voice might be recognized, thereby giving away their identity. Because Interval Research Corporation is a relatively small community where most people know one another, it was likely that privacy could be compromised in this way, perhaps with more embarrassing consequences than could be found in a more anonymous user population.

Also, people did have problems with the interaction itself. The most salient, once the other bugs had been ironed out, was their inclination to stare at the flame and think about what they wanted to say. This was not how the interaction was designed; recording began when the candle was lit so recordings of silence were not uncommon.

We were not really surprised by the feedback, it brought home to us how difficult it is to deal with these kind of issues. We concluded that while people could associate with the intention of the altar, it would be very difficult to get them to participate in a genuine and regular manner.

Based on this experience, there are a number of observations regarding the attempt to create a spiritual artifact involving ritual. Religious rituals have been around so long that the activities or tasks involved have become accepted and unquestioned in terms of procedure. We were trying to get people to perform a task that was new and unfamiliar. This presented interaction difficulties and questions arose as to why it should be done ‘this way’ verses ‘that way.’ It would be interesting to see whether people become familiar enough with the candle altar over time to accept it into their own rituals. This would only be possible if the ritual itself was considered worthwhile.

In contrast to the Cross exhibit at the NME2, which gave people immediate gratification for their actions, the candle altar’s value lies in its usage over time. It was impossible to simulate the effect in the short time we had to display it. It would be good to install it in a setting where it was used regularly and for a long time. However, some issues need to be addressed before considering such an installation.

Distinctions, identity, and anonymity

· A number of people suggested that we might want to add context to the flames. Possible context might include the date, an image of an object, or who left the flame. This is a tricky issue because we also had people asking for greater anonymity. They wanted their voices disguised.

· It was suggested that rather than being a spiritual artifact it could be for people who had a shared experience or condition (such as AIDS).

Environment and context

· Some people wanted the station to be more private or to allow them to whisper their message.

· Maybe the installation should be in a very public space (not a community) so that the voices would remain anonymous.

· It was noted that the angular shape of the installation’s top evoked thoughts of churches

Creation vs. Consumption

· It was suggested that this might be a nice tool for browsing existing story spaces. A number of people suggested stories from Holocaust survivors, including Steven Spielberg’s “I remember” project.

Interaction

· Some people wanted to light the candle first and then put it down.

· There was a desire to spend more time touching the installation without going through the message recording process.

· People found the interaction of lighting and immediately recording a message non-intuitive. They naturally wanted to stare into the flame and compose their thoughts before speaking.

These are all open issues that could only be resolved with more research and development involving people using the altar. This raises the issue of how existing rituals came to be and how they evolve over time. Further development would require feedback from users who have genuinely adopted the altar into their spiritual practice.

7.3 Possible enhancements and conclusions

Enhancements could be made in a number of areas, including interaction, purpose, target users and environment. The interaction, for example, could be improved by matching the sequence and nature of the events with people’s expectations. However, we feel that improvements to the interaction would not address several more important issues.

It was obvious that the altar did not work as intended, perhaps because it was situated in an exhibit with other NME2 designs. People interacted with it out of curiosity, not spiritual need or devotion. And, because it was new to them, they required explanation of what it was for, why they should use it and how to use it. Also, we think that the altar may have been too broad in its raison d'être. It was intended to provide people with a means of externalizing a problem or event that had spiritual significance to them. This benefit is only available to the individual if they value this kind of disclosure and if they are comfortable with the specific parameters of the interaction. Based on the user feedback, the installation of the altar in the CAVE did not match people's values and expectations. Although they were receptive to the potential benefits provided by externalizing their thoughts, people weren't sure if they were supposed to talk about personal problems, commemorate events, or leave pithy comments. They were also unsure about the spiritual value of the activity, confused about the reason for the automatic commemoration, and questioned the wisdom of giving colleagues access to their messages.

We feel that if we targeted a particular community, and better framed the altar as a means of sharing issues relevant to them, it may be better received. The functionality and the specifics of the interaction could be modified to make the target users comfortable adopting the altar as a part of their spiritual practice. Of course, if the subject matter was anything other than spiritual, or related to Christian beliefs, the artifact's appearance would have to be revised. As is, the look is reminiscent of places of worship, specifically Christian churches.

Appendix A: Design Development

The next section addresses three areas of the development process: content, technical and physical. They should provide an insight into how the design was shaped by a combination of vision and solutions to problems encountered during development. Incidentally, it nicely illustrates the non-linearity and semi-structured nature of design.

Please bear in mind that our design goal was to give people the feeling of lighting a real candle and enable them to leave a meaningful ‘message’ in a natural way, all without obvious technological intervention.

Nature of message

The following ideas were evaluated for ease of implementation, interaction complexity and value of message type.

· capture video of candle supplied by user

· record audio

· scan paper with message/photo

· video image of person or object they bring

Capturing an audio message seemed to score highest with these criteria.

What to display including behavior and differentiation

We had to design for a situation when the screen would be filled with different candle messages. These could be arranged in a matrix, on virtual shelves or in a random array. The latter method seemed the only way to accommodate unpredictable numbers of candles and if they were to move slowly, randomly around the screen they would not permanently occlude nearby candles.

Possible image types that we could display were:

· video of real candles or just flames burning

· representations of candles or flames burning

· abstract representations of flames

Of these the abstract images seemed the most appropriate because they would not be processor/memory intensive and would not be subject to realism critique which could conceivably be detrimental to the user experience.

Lighting a candle

Our initial solution to this was to simulate the lighting of a candle by replacing a candle wick with a heat detector and when a match is put to the ‘wick’ display a flame on the monitor directly behind the candle. This raised a number of problems:

· Parallax between candle and screen would be an issue depending on the viewing angle and height of the person. A partial solution to this was to set the candle and monitor back into an alcove to reduce the angle at which a person could see the candle. This idea helped inspire the design of the final artifact in that the image that sprang to mind was of a church-like wall with a deep alcove perhaps made of stone.

However, we concluded through experimentation that the experience would always be compromised by incorrect registration of flame and candle from the viewer’s point or view.

· Secondly we tested the response time of a thermocouple and found it to be too slow to detect a flame and consequently cause a flame to be displayed on screen.

Sensing a flame

One of the hardest technical issues we addressed was the sensing of a flame. Since flame detection was an important part of our interaction story, we wanted to have a robust technical solution. The problem can be broken down into three states: the lighting of the flame, ongoing flame, and blowing out the flame. Our initial concept was to use a thermocouple to detect temperature change created by a lit flame. After early exploration of this idea, we found that the response time was too slow. Our next attempt at flame detection was done with a photocell detecting light levels. We started by orienting the photocell perpendicular to the flame. This produced reasonable results but didn’t allow for varying candle heights. We also found that we were getting false positives if a person wore a brightly colored shirt or if a match was struck in sight of the photocell. Some improvement was achieved by removing reflections by putting the photocell at the end of a short, black tube. However, we still experienced false positives.

To address height issues, we decided to change the orientation of the photocell by putting it above the candle, aiming down. This allowed us to use varying heights of candle and gave us more control over the lighting on the surface behind the plane of the candle. Once orientation was resolved, we began to tackle the problem of false positives. Our initial set-up connected the photocell directly to an IRC11. The director movie read light levels directly from the IRC11 by polling during any idle cycles. We were not separating out the lighting of the flame from the other states. To correct for false positives, we implemented a running average with a variance delta and a trigger threshold. On start-up, the system found the ambient light level and used that as a baseline. In the first stage; lighting detection, a queue of 15 levels was maintained. If the most recent light level was above a certain value, the variance of the min and max of values in the queue were compared. If the difference was less than a given delta value, we knew that we had a stable flame. The variance on the queue provided us with stability information while the light level provided state information. This prevented false positives from lighting flare ups created by striking a match near the candle or matches held near the candle while lighting. Detection of the flame being blown out was much simpler. Once we knew that the flame was present, we simply looked for the light level to return to the baseline level (with some minor variance) measured on start-up of the Director movie.

Active Object Candles

Our method for identifying candles was very basic. Each candle had a resistor embedded in the bottom with one end of the resistor forming a spring in the center while the other end was placed at the edge of the candle. Candles were then placed on a pair of concentric copper plates, one small circle in the center, with a larger ring on the outside. The resistor completed the open circuit connected to the copper ring and circle. The circuit was connected to the IRC11. Differentiating between candles was accomplished by measuring the resistance across the circuit (with allowances for minor variances).

Software

The software was written in BC on the IRC11 and Lingo in Director for the Macintosh. The IRC11 code was a loop that waited for a polling request across the serial port. At each request, the IRC11 replied with the values of the light sensor and the candle circuit resistance.

The Director project was executed as a finite state machine with five states: an idle/start state, NewCandle, CandleLit, CandleOut and RemoveCandle. The program starts in the idle state by displaying and animating any existing virtual flames. When a virtual flame is touched, the associated audio is played. Transition from that state to NewCandle occurs when a new candle is placed on the copper disc. Transition from NewCandle to CandleLit occurs when a flame is detected. At that point, the system begins to record audio. Transition from CandleLit to CandleOut occurs when the flame is blown out. The audio recording is stopped and the audio is played back to the guest. If the guest lights the candle again, the system transitions to the CandleLit state again. Removing the candle transitions to the RemoveCandle state. The audio is recorded on disk and the new virtual flame is added to the database. After completion, the system transitions back to the idle state and displays appropriate virtual flames.

Once we settled on the concept of ‘some kind of candle altar’ it was important to consider the environment and circumstances in which the installation would be exhibited so as to produce the most effective and appropriate instantiation.

We wanted to produce an artifact reminiscent of some religious institution without being too denominationally biased. We felt material choice was crucial to the experience and wanted, in particular, a feeling of antiquity and stability - stone fulfilled this criteria. The next step was to source the materials. The best stone-like material turned out to be stone-effect ceramic tiles in 6x6, 6x12 and 12x12 inch sizes.

|

|

The limitations in cutting tiles were a key consideration in the final design. Consequently a design utilizing 45° and 90° angles and measurements based on tile size was developed. To check proportions, appearance, and physical affordances we built a full size foam core model of the facia and shelf. This model was subsequently used for all the development and debugging of the electronic components of the design while the real artifact was built. This proved to be a very useful design tool. |

A4 Initial Public Release and Revisions

The first day of the exhibit in the CAVE proved pretty disastrous! As usual, real people did totally different things to what we’d expected, using either a different sequence of tasks or totally unanticipated actions and even discovering a property we did not know existed. The combination of this and an unreliable flame detection system meant that very few people completed the tasks successfully.

It should be said that there were no instructions on the installation. We were relying on people to guess the first step given the limited options and then be prompted through the rest by the audio instructions. We did attend the installation at the beginning but did not generally help people. The main reason for failures was the erroneous flame detection.

Here are the main problems encountered and their subsequent solutions:

· Many people lifted the candle to light it, which reset the system. When the candle was replaced on the copper disc, the ‘light candle’ instruction was played which confused people as the candle was already lit. To compensate for this we changed the code to skip the first prompt if a candle and flame were detected simultaneously.

· False recording start due to match flare being confused for a lighted candle. When the flare died down the system stopped recording and played the instruction for the next step. This was dealt with by improving the flame recognition algorithm by introducing delta values, etc.

· White squares were appearing instead of flame representations. This was an oversight related to the number of sprite channels in Director which were not prepared for containing flame sprites. Unfortunately it took a while to realize what the problem was!

· People bridged the gap between the two plates with their hands. As the focal point of the shelf, touching the discs seemed a natural thing to do. However, those that did were identified by the system as a yearly candle and told to light the candle! As a result, some people lit one of the candles where it stood at the side of the shelf and of course failed to achieve anything. We introduced a software filter to differentiate the yearly candle and human skin and now play the following prompt if anyone touches the disc: “Choose a candle and place it on this disc.”

DH:

I don't think of myself as having any rich, religious experience with candles

(having grown up in a Methodist church). I recorded a blurb about how the candles

reminded me of Christmas Eve services at my church when the congregation is surrounded

by a choir holding candles, which are the only source of light in the church.

Afterward, I thought of something that might have been more personal and meaningful to me. For me, one of the ways that my faith is strengthened is by remembering God's faithfulness to me in the form of answered prayers. Suppose I had a set of candles, each of which represented a prayer request. When a prayer was answered, I could annotate the original request and record how and when it was answered. The flames on the screen that represent answered prayers could be a different color. Or maybe I'd want to be able to do some sorting -- for example, be able to see all the flames representing one category of prayers - like those for my immediate family (vs. me, or friends, or extended family, etc.)

I tend to forget how many times and in how many different ways God has done something for me. I've got a small collection of garden rocks and I'm creating a rock garden of answered prayers for my daughter. There were two special times last year that she prayed for something and God answered her prayers, so there is a rock for each of those. And there is a rock with her name on it as she is also an answer to prayer. This same idea could be implemented using your candles.

RG:

One last comment, the candle exhibit was also great. However, I felt uncomfortable

recording my voice. I think this was for two reasons: I did not see the spiritual

connection between recording my voice and spirituality. The second, candle lighting

is often a silent act, and praying a whispering act unless one is with others.

BN:

The Candle Box: nice idea, but I thought the idea of "monthly" "weekly"

"daily" was unnecessary. Just having the candles record messages is

enough to me, and the intervals of replaying them seemed distracting to what should

be a very personal experience..

AH:

I thought the "Light

a Candle" piece was nicely done, though I wanted to be able to find my "flame"

amongst the others after recording it. That was difficult without putting too

much time into it and it felt invasive to hear others' words that seemed private.

That is interesting though as once you light a candle in a church and say your

blessing or prayer you don't hear it again - kind of a one time deal. Why did

I want to hear my words again, I wonder? Perhaps the fact that I "could"

hear my words again, due to the technology involved, made me want that.

DC:

I liked the candle memorial. The automatic repetition of spoken recordings at regular intervals gets at the idea of ritual in spirituality. It stretches ritual so far as to be absurd, as if the computer would continue to recite the phrases long after people forgot. A nice reflection on an aspect of religion and spirituality.

I felt strange about recording something as it felt exposed and my reaction was to not do it at all (so as not to risk embarrassment). Some level of comfort/camaraderie/privacy needs to be reached before the more reserved people feel open.

Appendix C: History of Candle-making and Candle Industry Facts [1]

For centuries, candles have cast a light on man's progress. However, there is very little known about the origin of candles. Although it is often written that the first candles were developed by the Ancient Egyptians who used rushlights, or torches, made by soaking the pithy core of reeds in molten tallow, the rushlights had no wick like a candle. It is the Romans who are credited with developing the wick candle, using it to aid travelers at dark, and lighting homes and places of worship at night.

Like the early Egyptians, the Romans relied on tallow, gathered from cattle or sheep suet, as the principal ingredient of candles. It was not until the Middle Ages when beeswax, a substance secreted by honey bees to make their honeycombs, was introduced. Beeswax candles were a marked improvement over those made with tallow, for they did not produce a smoky flame, or emit an acrid odor when burned. Instead, beeswax candles burned pure and clean. However, they were expensive, and, therefore, only the wealthy could afford them.

Colonial women offered America's first contribution to candle-making when they discovered that boiling the grayish green berries of bayberry bushes produced a sweet-smelling wax that burned clean. However, extracting the wax from the bayberries was extremely tedious. As a result, the popularity of bayberry candles soon diminished.

The growth of the whaling industry in the late eighteenth century brought the first major change in candle-making since the Middle Ages, when spermaceti, a wax obtained by crystallizing the spermaceti wax did not elicit a repugnant odor when burned. Furthermore, spermaceti wax was found harder than both tallow and beeswax. It did not soften or bend in the summer heat. Historians note that the first "standard candles" were made from spermaceti wax.

It was during the nineteenth century when most major developments affecting contemporary candle-making occurred. In 1834, inventor Joseph Morgan introduced a machine which allowed continuous production of molded candles by the use of a cylinder which featured a movable piston that ejected candles as they solidified.

Further developments in candle-making occurred in 1850 with the production of paraffin wax made from oil and coal shales. Processed by distilling the residues left after crude petroleum was refined, the bluish-white wax was found to burn cleanly, and with no unpleasant odor. Of greatest significance was its cost -- paraffin wax was more economical to produce than any preceding candle fuel developed. And while paraffin's low melting point may have posed a threat to its popularity, the discovery of stearic acid solved this problem. Hard and durable, stearic acid was being produced in quantity by the end of the nineteenth century. By this period, most candles being manufactured consisted of paraffin and stearic acid. With the introduction of the light bulb in 1879, candle-making declined until the turn of the century when a renewed popularity for candles emerged.

Candle manufacturing was further enhanced during the first half of the twentieth century through the growth of U.S. oil and meat-packing industries. With the increase of crude oil and meat production, also came an increase in the by-products that are the basic ingredients of contemporary candles -- paraffin and stearic acid.

No longer man's major source of light, candles continue to grow in popularity and use. Today, candles symbolize celebration, mark romance, define ceremony, and accent decor -- continuing to cast a warm glow for all to enjoy.

· U.S. candle consumer retail sales are currently approaching two billion dollars annually, not including candle accessories. Since the early 1990's, the industry has been growing at a rate of 10% - 15% annually, with even greater growth in the past 2-3 years.

· There are over 100 known commercial, religious and institutional manufacturers of candles in the United States, as well as many small craft producers for local, non-commercial use.

· Candles are sold principally in three types of retail outlets: department stores, specialty (gift) shops and mass merchandisers, including drug store chains, supermarkets and discount stores. The U.S. market is typically separated into seasonal (Christmas Holiday) business at roughly 35%, and non-seasonal business at about 65%.

· Typically, a major U.S. candle manufacturer will offer 1,000 to 2,000 varieties of candles in its product line.

· Types of candles manufactured in the U.S. include: tapers, straight-sided dinner candles, spirals, columns, votives, wax-filled containers, and novelties. Some of these varieties come in different sizes and fragrances, and all come in a range of colors.

· Candles range in retail price from around $.20 for a votive up to $75.00 for a specialty or large column candle.

· Candle shipments increase substantially during the third quarter of the year because of the seasonal nature of candle sales for the Christmas season.

· Historically, production workers have represented approximately three-fourths of the total employment in the candle industry.

· Candle industry research findings indicate that the most important factors affecting candle sales are color, shape and scent. Fragrance is increasing in importance as a special element in the selection of a candle for the home.

· Candle manufacturers' surveys show that 96% of all candles purchased are bought by women.

Appendix D: Exhibition Hand-out

Candle stories

Babel

Oliver Bayley and Sean White

While older technologies like the printing press and the television have been accepted by many religions and spiritual practices as a basic part of the tradition, new technologies are often considered antithetical to the notion of spirituality. Candle Stories explores the interaction between the new and the old by facilitating existing religious rituals through technological means.

The glowing lights contain messages, which may take the form of commemorations, prayers or wishes, which have been left over the course of many years. Some lights occur only once a year on a special day while others occur daily. The special meaning of each light can be heard by touching it.

To create a light:

1. Place a candle in the center of the copper disc. Each candle represents a cycle of time. From largest to smallest, they represent yearly, monthly and daily cycles.

2. Light the candle

3. Speak your message and when you are done, blow out the candle

4. If you like what you have said, remove the candle and the message will be added

5. If you want to change it, light the candle and start again

There is no accurate record of the first candle, although many people believe that candles have been around since the Egyptians in 3,000 BC. Candles have been used as a tool or artifact in many rituals and religions over the years. Paganism, Christianity and Judaism are just a few of the traditions that have rituals which include the lighting of candles.

[1] Courtesy of the National Candle Assn., 1200 G. Street, Suite 760, Washington, DC 20005, (202) 393-1780, http://www.candles.org/.